I always got confused when a paper asked, “What was your first language?” I didn’t have one language, I had two. For as long as I could remember, I was spoken to in English and in Spanish. My parents had immigrated in their teens with my grandparents to the United States. By the time their first-generation Dominican-American baby was born, they had mastered the language. My first language became Spanglish.

I always got confused when a paper asked, “What was your first language?” I didn’t have one language, I had two. For as long as I could remember, I was spoken to in English and in Spanish. My parents had immigrated in their teens with my grandparents to the United States. By the time their first-generation Dominican-American baby was born, they had mastered the language. My first language became Spanglish.

My mother was so upset when I was put into bilingual kindergarten. “She SPEAKS and UNDERSTANDS both languages,” she told the school angrily. But I was stuck for the year in Ms. Garcia’s class and I felt at home hearing Spanish and English blending together around me. My hair pulled back severely into two tight moños (buns), wearing my little dress and packing a Thundercats lunchbox, I spoke English with a slight Spanish accent. “Can I have some schocolate, Mami?”

My first grade teacher couldn’t pronounce my name. I had jumped into the top English-only class. She stumbled, trying to roll her r’s and gave up. She sounded it out in “American” and with it, Americanized me. I had an “English” name and a “Spanish” name. And despite the fact that my classmates would rhyme my “American” name with diarrhea, I loved it.

“You have an accent,” a little Greek girl told me in the lunchroom. I turned bright red with embarrassment. I had seen how my mami’s accent affected her. People pretended not to understand her at the welfare office. They spoke to her slowly in English. As if she didn’t have a college education! But by the end of the fifth grade, my accent had been obliterated by elementary school.

Aliza graduates from bilingual kindergarten.

“You talk like a white girl. You think you’re better than us, white girl?” taunted Jose, the leader of the bullies that had dubbed me and my friends “Nerd Patrol” in junior high school. I blamed looking like a white girl on my pale father but it was my mother’s fault that Jose and his goons thought I sounded like one. “What did you say?” she asked when I walked in the door later that day. “I said, Mom, you won’t freaking believe what happened to me, man,” I repeated rolling my eyes. She slapped me. “I don’t want you talking like those tigeritos (hoodlums) on the street. There will be no slang in this house.” I opened my mouth to protest that I had picked it up from Bart Simpson, not those tigeritos but closed it quickly. But no one talked back to my mother.

In college, none of the Hispanic kids would play with me. All of them had bonded over a summer together in a program geared towards preparing them for college. I had tested out because of a high SAT Verbal score. “You’re half-white, right?” my cute Mexican classmate of the soft, sooty eyelashes asked me. “What?” I asked incredulously. “Well, you talk white and you never speak any Spanish.” I narrowed my eyes. Disgusted. Felt like I was back in high school being told that Dominican meant “dumb-in-a-can.” If Hispanics weren’t going to accept me for who I was then I didn’t care if I was one of them.

“You don’t have to speak Spanish to be Hispanic,” our “Hispanic Women 101” profesora (professor) told the class. Until then, I hadn’t realized there were enough Hispanic people to fill a room at my college. We read books and plays by Hispanic authors. We talked about language, race and culture. About who was Hispanic, what Hispanic was and wasn’t. And suddenly, it wasn’t those tigeritos making fun of me, those self-hating kids in high school or the trash talkers who thought anyone unable to speak ghetto Spanglish wasn’t Hispanic enough. It wasn’t their birthright.

“Los tienen en marrón?” (Do you have them in brown?) I ask the Hispanic guy at the shoe store. He responds tersely in English. I blush. Maybe he thinks I thought he didn’t speak English. I shake it off. I’ve decided to speak Spanish anywhere and everywhere I can. At the supermarket, I ask for platanos. At the post office, I yell at the clerk in rousing Spanglish. And I take the Dominican gypsy cabs all over Manhattan and the Bronx, practicing rolling my tongue over those r’s and multisyllabic words. “You’re Dominican?” they ask, turning around in their seat to get a better look at me. “Si,” I respond, asking them where they’re from, telling them where my parents are from. We chat effortlessly (“¿Um, como se dice “writer” en Español?” I ask.) during the rest of the ride.

The plight of many of my Puerto Rican friends has been losing the language. “It’s, like, my mother barely spoke Spanish, you know, how was I supposed to learn?” And then I realize I have it easy. Spanish hasn’t been entirely lost in my family. It’s the only mode of communication for speaking to my abuela (grandmother), my 95-year-old bisabuela (great grandmother) and my Tia (aunt) who called me a gringa for showing up on time for my cousin’s baby shower. “Don’t you know Dominicans never show up on time?” she whispered in flawless Spanish.

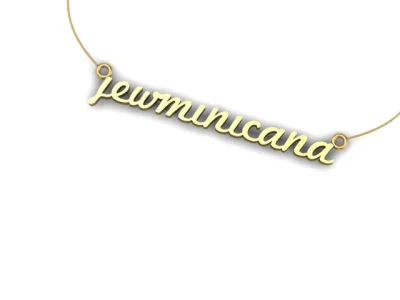

I tell my Dad I’m getting married in English because it wouldn’t be as funny in Spanish. “He’s what?” my Dad yells over the static on the connection of our international call. Dad lives in Santo Domingo but refuses to speak to me in anything but English. “I don’t care if you don’t speak Spanish. We both speak English, right?” he shrugs. “He’s white. Jewish.” There’s a pause. “Does he speak Spanish?” I tell Dad that he doesn’t but that he makes really good arroz con habichuelas (rice and beans). Laughter erupts on both sides.

But the truth is that I’m scared. “How will our kids speak Spanish?” I ask my husband on one of those days when I picture my ancestors wagging their fingers down at me from heaven because my imaginary children can’t speak to their Spanish-speaking cousins in “DR” (the Dominican Republic). “I want to learn to speak Spanish,” he says. And he means it. He signs up for classes. He muddles through the Spanish-language newspaper. He listens to Juanes and Marc Anthony. He already speaks Spanglish. But he won’t agree to watch novelas (Spanish-language soap operas) for practice. But then, he won’t watch Grey’s Anatomy either.

I’m 28 years old and I’m holding a Dr. Seuss book in Spanish and English from the library. I picked it up after I had to put down a Julia Alvarez book for the grade school set. It was too hard. I have my trusty Franklin electronic translator by my side. And a promise. That my kids will speak Spanish. That they will know and understand where they come from. That they’ll be proud of being Hispanic. Even though there mother once was not.

Ladino, my dear. Ladino! That would be an interesting and amazing way to have Spanish and Hebrew around the house. Plus, there’s a mini-revival going on from what I can tell. It’s a lost language, and from what I’ve heard and read, it’s quite beautiful. This was a wonderful piece. You’re a truly amazing writer 🙂

LikeLike

From your lips to G-d’s “ears” and back down to the Latina Editor-in-Chief who would have to okay my little piece for an upcoming issue.

LikeLike

America, as a culture, tends to allow immigrant populations to maintain their food and culture, but it exerts a great deal of pressure to speak English. See the fate of Yiddish for another example.There’s no reason why you couldn’t raise bilingual children. There are tons of Jewish communities in South America anyway, it might come in handy.I’m a native English speaker, and I’m hoping to raise my children bilingual Italian/English speakers. I know it can be done, I have plenty of friends who were raised bilingual. There are no lasting effects on a child’s ability to speak, read or write their mother languages or any other languages if they are bilingual.

LikeLike

My youngest sister speaks no Spanish despite being raised around English and Spanish speakers. I think my task will be to surround myself who speak Spanish as a native language so that they will have people to talk to in Spanish other than their parents. This becomes harder with family members in my generation, all with the exception of family members in the “motherland” speak English and very poor Spanish.

LikeLike

Well it’s interesting because my 7 year old son, whom we adopted in Guatemala when he was an infant, has started to openly identify himself as being Hispanic, which he sometimes pronounces as “Hi-panic”, and articulate the fact that, as he puts it, “he is brown.” Our boy attends a Modern Orthodox Day school in suburban Chicago where he is the sole representative of “Latino USA” among the student body. We’ve tried to remind him of his heritage. Last September, when Guatemala’s “Dia del Independencia” rolled around we sent treats to school for him to share with his classmates. This didn’t go over well with his Judaic Studies teacher who openly questioned the wisdom of celebrating a Latin country in a very Zionist Day school. Our Rabbi, a Franco-Tunisian, in sharp contrast fully supported us on this.When we brought “El Nino, El Corazon” home my wife and I were determined to learn Spanish and introduce that into his life. That has fallen by the wayside over the years but the lad is finding his way as being doubly blessed by two amazing heritages. He even told me that he wants to go back to Guatemala for his Bar Mitzvah. All the best!

LikeLike

It’s the same anon as above–I’ve noticed that with younger children in immigrant families, they often end up in the position of being able to understand, but not reproduce their parents’ native language. I have a friend whose mother speaks to him in a dialect of Chinese–he can understand it, but can only answer her in English.

LikeLike

Quite true. Though, I’m pretty sure that my sister doesn’t understand English either. She’s about 15 years younger than me. And I suppose by the time she was born, English had far outweighed Spanish in the language we used at home.Something interesting to note. My husband’s cousins who are not native Spanish speakers attended a immersion school and speak and understand Spanish to this day as adults. The youngest of the three siblings understands more than he can speak.

LikeLike

quizás yo y tu marido podremos hablar en nuestro español débil este año que viene en la yeshibá 😛

LikeLike